#Abu Ama

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Abu AMA - Intuitiv - the closest thing to vintage 23 Skidoo you'll hear this year

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Invisible Club 022

17.07.2024

Intro 00:00 Scott F. Hamrick-Of Ends and Means 01:27 Conny Frischauf-Ballooooon 05:47 Abu Ama-Blade Runner 08:21 Einseinseins-Gasetagenheizung 13:02 Volker Rapp-Mercerism 17:53 Saša Delimar-What is the Full Meaning of This 21:43 2muchachos-Vremja Tepla 28:29 Steve Cobby-Silent Windmills 32:27 Sababa 5, Yurika Hanashima-Empty Hands 38:11 Joakim Moesgaard-Eusement 41:27 silentwave-Hakaba Night 44:15 Gaussian Blur-Some Heavy Load 50:06 Karl Marx Stadt-You Know You Want To (Remix) 50:57 Dub Atomica (Ian Boddy & Nigel Mullaney)-Atomicity 54:54 Secret Circuit-Galleon In The Clouds – Froid Dub Rmx 1:04:13 Unknown Me-Retreat Beats 1:08:17 Outro 1:12:04

#Scott F. Hamrick#Conny Frischauf#Abu Ama#Einseinseins#Volker Rapp#Saša Delimar#2muchachos#Steve Cobby#Sababa 5#Yurika Hanashima#Joakim Moesgaard#silentwave#Gaussian Blur#Karl Marx Stadt#Dub Atomica#Ian Boddy#Nigel Mullaney#Secret Circuit#Unknown Me#Bureau B#Mahorka#echodelickrecords#Cyclical Dreams#Secuencias Temporales#Not Not Fun Records#Déclassé#Batov Records#Moniker Eggplant#Móatún 7#Intellitronic Bubble

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sensational VS Abu Ama

#sensational Sensational If you don’t know by now step correct and re-frame Sensational of Crooklyn fame: subterranean lyrics over over lo fi dub noise beats, same as it ever was.Originally grazing with Wordsound label, post apocalyptic illbient stable, alongside Bill Laswell rocking blue light torch of avant-garde hip hop and bass music since 1999, here comes Sensational VS Abu Amu with 2…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#kat abughazaleh#Katherine Abughazaleh#kat abu#us congress#women in politics#women in congress#gen z#gen z girls#cat#😺#april 10#ama#instagram

1 note

·

View note

Note

ask de @ratoderua : qual a sua opinião sobre os direitos dos macacos? você prefere papagaios falantes ajudantes de vilões ou macacos estilosos que gostam de adrenalina?

❝ São importantíssimos! Eu era bem porta-voz disso no twitter aliás, antes do reino dos perdidos. Macacos são muito maltratados no meu mundo, um completo absurdo. Papagaios falantes são divertidos, mas é claro que macacos estilosos são muito mais! Especialmente se for o Abu. Te adoro, Abu! Um beijo. ❞

#𝗳𝗶𝗹𝗲𝗱 𝘂𝗻𝗱𝗲𝗿 ⇢ tasks: acabando a mamata.#lostonesinterview#não é puxação de saco#ela só genuinamente ama o abu

1 note

·

View note

Text

🚀 Elevate Your Online Presence with CodenDream! 🌐✨

Hey, dreamers! ✨ Ready to take your online journey to the next level? CodenDream has something special just for you! 🚀

🌟 Introducing our exclusive offer: Get a FREE Dot XYZ Domain with every web hosting plan! 🌐✨

Why settle for ordinary when you can stand out with a unique domain extension? 🔍 Whether you're starting a blog, launching a business, or showcasing your creative genius, CodenDream has got you covered!

🎁 What's in it for you? ✅ FREE Dot XYZ Domain ✅ Powerful Web Hosting Plans ✅ Unleash Your Creativity Online

👉 Ready to claim your free domain and dive into the limitless possibilities of the web? Head over to CodenDream and let your digital dreams take flight! 🚀💻

🔗 Visit

#CodenDream #WebHosting #DigitalDreams #FreeDomain #DotXYZ #OnlinePresence #WebDevelopment #ClaimYourDomain #DreamBigOnline ✨

#mosab abu toha#excerpts#rainer maria rilke#literature#essays#victoria chang#quote#ama asantewa diaka#poetry#woman eat me whole#out of my collection#saturday evening whatsapp message#brenda hillman#in a few minutes before later#escape & logic

0 notes

Text

“From the River to the Sea.” A Poem by Samer Abu Hawwash, translated by Huda Fakhreddine

every street, every house, every room, every window, every balcony, every wall, every stone, every sorrow, every word, every letter, every whisper, every touch, every glance, every kiss, every tree, every spear of grass, every tear, every scream, every air, every hope, every supplication, every secret, every well, every prayer, every song, every ballad, every book, every paper, every color, every ray, every cloud, every rain, every drop of rain, every drip of sweat, every lisp, every stutter, every yamma, mother, every yaba, father, every shadow, every light, every little hand that drew in a little notebook a tree or house or heart or a family of a father, a mother, siblings, and pets, every longing, every possibility, every letter between two lovers that arrived or didn’t arrive, every gasp of love dispersed in the distant clouds, every moment of despair at every turn, every suitcase on top of

every closet, every library, every shelf, every minaret, every rug, every bell toll in every church, every rosary, every holy praise, every arrival, every goodbye, every Good Morning, every Thank God, every ‘ala rasi, my pleasure, every hill ‘an sama’i, leave me alone, every rock, every wave, every grain of sand, every hair-do, every mirror, every glance in every mirror, every cat, every meow, every happy donkey, every sad donkey’s gaze, every pot, every vapor rising from every pot, every scent, every bowl, every school queue, every school shoes, every ring of the bell, every blackboard, every piece of chalk, every school costume, every mabruk ma ijakum, congratulations on the baby, every y ‘awid bi-salamtak, condolences, every ‘ayn al- ḥasud tibla bil-‘ama, may the envious be blinded, every photograph, every person in every photograph, every niyyalak, how lucky, every ishta’nalak, we’ve missed you, every grain of wheat in every bird’s gullet, every lock of hair, every hair knot, every hand, every foot, every football, every finger, every nail, every bicycle, every rider on every bicycle, every turn of air fanning from every bicycle, every bad joke, every mean joke, every laugh, every smile, every curse, every yearning, every fight, every sitti, grandma, every

sidi, grandpa, every meadow, every flower, every tree, every grove, every olive, every orange, every plastic rose covered with dust on an abandoned counter, every portrait of a martyr hanging on a wall since forever, every gravestone, every sura, every verse, every hymn, every ḥajj mabrur wa sa ‘yy mashkur, may your ḥajj and effort be rewarded, every yalla tnam yalla tnam, every lullaby, every red teddy bear on every Valentine’s, every clothesline, every hot skirt, every joyful dress, every torn trousers, every days-spun sweater, every button, every nail, every song, every ballad, every mirror, every peg, every bench, every shelf, every dream, every illusion, every hope, every disappointment, every hand holding another hand, every hand alone, every scattered thought, every beautiful thought, every terrifying thought, every whisper, every touch, every street, every house, every room, every balcony, every eye, every tear, every word, every letter, every name, every voice, every name, every house, every name, every face, every name, every cloud, every name, every rose, every name, every spear of grass, every name, every wave, every grain of sand, every street, every kiss, every image, every eye, every tear, every yamma, every yaba, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, all…

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

G.I Incorrect Quotes#86 They were roommates...

Three roommates...trying to raise the next Dendro Archon...could this be an au?...

Baby Nahida: Mah...

Alhaitham*Looking at his child*No

Baby Nahida*Glares at Papa*abUA ama bu!

Alhaitham*Frowns at the baby deity*Dont you talk back to me

Baby Nahida*Starts pounding her tiny fists on his chest in a tantrum*ABU!BUH BUH!

Alhaitham: I said "NO" and I overrule you, young lady

Y/n*Knitting for Nahida a onesie* Would you please stop arguing with our child...and next Dedron Archon

Alhaitham:...I might as well, I think she's winning...

Kaveh*Coming in and picking her up happily, taking her to the board and giving her the chalk*Aww~Look at you Nahida~Wanna add the point yourself?~

Baby Nahida*Gleefully with her chubby hand draws her four rows and cross them to make it a five...compared to Alhaitham who only has one*!!!~

Alhaitham:...

#genshin impact#genshin impact x reader#genshin#genshin x reader#genshin x y/n#roommates to parents au#genshin nahida#genshin alhaitham#genshin kaveh#alhaitham x reader#alhaitham x y/n#kaveh x reader#kaveh x y/n#alhaitham x reader x kaveh#alhaitham x kaveh#genshin fluff#genshin incorrect quotes#incorrect quotes

698 notes

·

View notes

Text

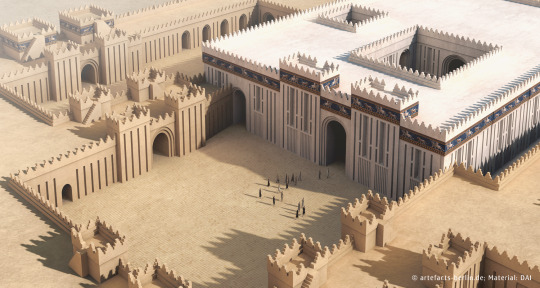

Pride Month special 2025: shifts in gender, shifts in character. A Mesopotamian deity triple feature

The following article, in addition to being a pride month special, is also the third installment of a series which started with Nonconformity, ambiguity, fluidity and misinterpretation: on the gender of Inanna (and a few others) and continued in Ninshubur(s), Ilabrat, Papsukkal and the gala: another inquiry into ambiguity and fluidity of gender of Mesopotamian deities. This time instead of looking at the gender of a specific deity or category of deities I’ll instead discuss three remarkable cases in which a deity’s gender shifted: a mourning goddess turned fire god; a second, originally female, Dumuzi (feat. two unique passages which are as close to non-subtextual Inanna f/f as we can get for now - caveats apply); and a divine clerk in the service of Inanna who went from god to goddess without any other apparent changes.

Note that while I previously said this will be the final installment of the series, I have since realized at least one more will be necessary - stay tuned for further updates.

For now, more under the cut, as usual.

From mourning mother to “the handsome one”: Lisin (and Ninsikila)

Lisin already appears in the Zame Hymns from Abu Salabikh (c. 2500 BCE), one of the oldest religious texts presently known. She is the last of the deities listed, and her corresponding cult center is ĜEŠ.GI (reading uncertain), possibly to be identified as Abu Salabikh itself (Manfred Krebernik, Jan J. W. Lisman, The Sumerian Zame Hymns from Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ With an Appendix on the Early Dynastic Colophons, p. 14). The hymn is fairly formulaic, and doesn’t say much about Lisin beyond her connection with ĜEŠ.GI. She is referred to with the title ama, literally “mother”, though it is unlikely that it should be taken literally. Instead it most likely functions as an indicator of her role as the tutelary goddess of the corresponding city (The Sumerian Zame Hymns…, 46).

A lament focused on Lisin (Lisin A; as you can see here it’s part of the ECSL system, but isn’t actually accessible online), written in first person from her perspective, portrays her mourning the death of an unnamed son, for which she blames her own mother, Ninhursag. She states that this event made her lonely, and that she has no friends or neighbors. The description of mourning itself is fairly formulaic, with all the expected mentions of tearing her own hair, performing lacerations, et cetera. While multiple copies are known, they are imperfectly preserved, and not much can be said about it beyond that (Christopher Metcalf, Sumerian Literary Texts in the Schøyen Collection, p. 52-56).

Lisin’s importance declined by the Old Babylonian period (c. 1800 BCE), if not earlier (Piotr Michalowski, Lisin in RlA vol. 7, p. 33). However, that was not the end of this deity’s history. At an uncertain point after the decline, the name was rediscovered by compilers of god lists. They correctly noticed that Lisin had a spouse, Ninsikila, but that was about it - not even the gender of those two deities was evident to them. Since Lisin typically comes first in older sources, up to the Old Babylonian period (Lisin…, p 32), the new generations of theologians concluded that the former must have been male and the latter female, effectively switching their genders around, as attested for example in An = Anum (Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, p. 103). To be entirely fair to them - in Old Babylonian sources listing couples together, such as the Nippur god list, the husbands pretty much always precede the wives (Goddesses in Context…, p. 80). It was a decent guess to make based on evidence available to them.

The cylinders of Gudea (wikimedia commons)

A second factor might have been the phonetic similarity between the name of Ninsikila and that of a goddess from Dilmun (Bahrain) at some point introduced to Mesopotamia (Lisin…, p. 32). Despite actually being named Meskilak, the latter could even be referred to as Ninsikila in Mesopotamian sources, as already documented in the long composition preserved on the cylinders of Gudea (Manfred Krebernik, Meskilak, Mesikila, Ninsikila in RlA vol. 8, p. 94). Lisin also developed a distinct new role as a fire deity in apotropaic magic, though it’s not certain if that first happened after the change of gender or before (Markham J. Geller, Healing Magic and Evil Demons. Canonical Udug-hul Incantations, p. 310; Michalowski favors a late date; Lisin…, p. 33). Through dubious linguistic exegesis relying on alternate sign values and homonymy - a favorite pastime of priests and other similar experts in the first millennium BCE - Lisin's name was provided with a new etymology, too. Both cuneiform signs forming it also had readings pertaining to fire (or at least were homonyms of signs which did), so as attested in an esoteric explanatory text (BM 47463) it came to be explained as “he who burns with fire”, “the burning one” or “he who burns an offering”. A further “translation” which arose as a result of similar inquiries was “the handsome one”, relying on the use of a homonym of the sign SI from Lisin’s name being a logographic representation of Akkadian banû (Alasdair Livingstone, Mystical and Mythological Explanatory Works of Assyrian and Babylonian Scholars, p. 60-61).

A Kassite period depiction of Nanaya on a kudurru (wikimedia commons) One final step in Lisin’s career was the incorporation into the court of Nanaya in Borsippa in the late first millennium BCE (Rocío Da Riva, Gianluca Galetti, Two Temple Rituals from Babylon, p. 192). In a single case, the two of them alone occur in a ritual (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 220). In another, Lisin is just one of many courtiers listed (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 192; Usur-amassu, who will be discussed later, shows up too).

Sadly, as far as I am aware no sources shed any additional light on how exactly the connection between Lisin and Nanaya was conceptualized. It was possible to establish how it most likely developed, though. Nanaya’s temple in Borsippa - the Euršaba (“house, oracle of the heart”) - shared its ceremonial name with a temple of Lisin (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 203). While Lisin’s original Euršaba was located in Umma, a city which didn’t even exist anymore by the first millennium BCE, it continued to be referenced in laments and, most important, has an entry in the Canonical Temple List (Andrew R. George, House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 157). We know that in late periods theological lists could be essentially strip mined for deities to integrate into a city’s pantheon, as well documented in Seleucid Uruk (Julia Krul, The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk, p. 261). It’s easy to imagine something similar happened in Borsippa as well. The original temple would doubtlessly be long forgotten by the late first millennium BCE, so a priest stumbling upon a reference to Lisin being worshiped there and concluding the local namesake temple is meant instead strikes me as entirely believable.

To be entirely fair, I think there’s a second possibility, though it doesn’t necessarily contradict that proposed by Rocío Da Riva and Gianluca Galetti. One of the rituals pertaining to Lisin’s new role in the Euršaba mentions a cultic installation dedicated to Nabu (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 193). Elsewhere, in astronomical texts, a star named after Lisin (Antares) is associated with Nabu and Borsippa, despite the origin of the name (Hermann Hunger, Lisi(n), RlA vol. 7, p. 32). Zachary Rubin argues that Lisin might accordingly be a stand-in for Nabu in a colophon from Borsippa which lists him together with Nanaya (The Scribal God Nabû in Ancient Assyrian Religion and Ideology, p. 70). However, the cult of Nanaya in Euršaba had no strong connection to Nabu to speak of overall (Goddesses in Context…, p. 282), and as far as I know that is the only house of worship in the city Lisin was introduced to.

From a modern perspective, the gradual shift from a dime a dozen mourning goddess to a one of a kind god certainly might feel almost like trans coding. Ultimately it’s pretty much entirely accidental, though - it’s doubtful anyone involved in Lisin’s theological transformations was aware of the full history of this deity.

(The other) "Dumuzi, she herself": Dumuzi-abzu

Tell al-Hiba, the ruins of Lagash, in 2016 (wikimedia commons) In the third millennium BCE, roughly at the same time when Lisin enjoyed a position of relative prominence in the Zame Hymns, the local pantheon of the state of Lagash included the goddess Dumuzi-abzu. This name can be translated as “good child of the abzu” (Gebhard J. Selz, Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt des altsumerischen Stadtstaates von Lagaš, p. 114). Something that needs to be addressed right off the bat is that the abzu is extremely unlikely to be personified in this case, and it’s virtually impossible Dumuzi-abzu is literally supposed to be the child of the literary character people usually think of today when they hear this term. Prior to the compilation of the Enuma Elish in the late second millennium BCE, which famously pairs Abzu and Tiamat as a theogonic couple, abzu was rarely, if ever, regarded as a deity as opposed to a location (Wilfred G. Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 217-218). In a number of sources from between the Early Dynastic and Old Babylonian periods it isn’t even consistently a designation of the watery subterranean domain of Enki/Ea, and might instead be described as mountainous (like in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta or the hymn Ishme-Dagan D). A variety of sources, including the Temple Hymns attributed to Enheduanna, use it as a poetic term for sanctuaries, making it potentially quite vague depending on context (The Sumerian Zame Hymns…, p. 95). What exactly does it entail in this specific case? Hard to tell, though there were many sanctuaries referred to with the term abzu in Lagash in the third millennium BCE, with Dumuzi-abzu possibly originating in one of them. Furthermore, interpreting the name as “good child of the sanctuary” would be a sensible parallel to fellow Lagashite deity Dumuzi-gu'ena, “good child of the throne room” (Akiko Tsujita, Dumuziabzu. A Goddess and a God, p. 8-9).

Dumuzi-abzu was the tutelary goddess of Kinunir (or Kinirsha), a lost city located somewhere in the proximity of Lagash (Goddesses in Context…, p. 61). We know very little about her character otherwise, though it can be safely assumed that she was closely associated with Nanshe and her daughter Nin-MAR.KI (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 116). Offering lists group her with the likes of Nindara, Ninshubur, Hendursaga and other figures of similarly moderate importance in this part of Mesopotamia (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 115).

At least in Lagash, Dumuzi-abzu’s name could be shortened just to Dumuzi (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 114). Manfred Krebernik actually proposed that every single reference to a deity named Dumuzi in Early Dynastic texts - not just from this one state, but also from sites like Tell Fara - pertains to her, and not to Inanna’s spouse, who at the time would be primarily known as Amaushumgalanna (Manfred Krebernik, Drachenmutter und Himmelsrebe? Zur Frühgeschichte Dumuzis und seiner Familie, p. 163-164). This might be too radical of an approach, though (Gebhard J. Selz, Dumuzi(d)s Wiederkehr, p. 215), and it has been suggested that even in Lagash at least in theophoric names Dumuzi might be, well, Dumuzi (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 116).

As of 2024, it remains uncertain when Dumuzi became the default name of Inanna’s spouse, though first unambiguous examples are available from the Sargonic period, and it can be established with certainty that it was used fully interchangeably with Amaushumgalanna by the Old Babylonian period (Jana Matuszak, Hanan Abd Alhamza Alessawe, A Sargonic Exercise Tablet Listing “Places of Inanna” and Personal Names, p. 37). This doesn’t really change the fact that Dumuzi himself “did not belong to the leading deities in any period of Mesopotamian history” and his inflated modern importance owes a lot to the Golden Bough and similar disreputable sources (Bendt Alster, Tammuz(/Dumuzi) in RlA vol. 13, p. 433-434). This is not the time and place for further exploration of this topic, though.

Dumuzi-abzu was eventually seemingly largely subsumed into Dumuzi, but that only happened after her decline as an actively worshiped deity after the Ur III period, which in turn was a result of the area of the former state of Lagash losing its importance (Dumuziabzu…, p. 11-12). The god list An = Anum from the Kassite period identifies Dumuzi-abzu as a male deity, and as one of the sons of Enki, with no reference to any associations with Kinunir, Lagash, or deities from its pantheon. This is presumably a result of a reinterpretation of the abzu in the name as Enki’s dwelling. The shift in gender meanwhile reflected confusion with Dumuzi (Dumuziabzu…, p. 10-12). Andrew R. George suggests that Dumuzi-abzu came to be understood as a title designating the regular Dumuzi during his annual stay in the underworld, based on a broader pattern of confusion between the abzu (in this context explicitly the domain of Enki/Ea, ie. a mythical subterranean sea) and the land of the dead (The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, p. 861). The apparent conflation of Dumuzi and Dumuzi-abzu resulted in at least one further curiosity relevant to this article. There is a unique love poem which addresses Inanna’s lover, who is left nameless through most of the composition, as Dumuzi-abzu, as opposed to simply Dumuzi. Sumerian has no grammatical gender, so technically it would not be impossible to translate the relevant passage as if the traditional female Dumuzi-abzu was the target of Inanna’s affection, though obviously this is not exactly a plausible interpretation (Bendt Alster, Sumerian Love Songs, p. 143).

Modern replica of a typical Mesopotamian lyre on display in the Iraq Museum (wikimedia commons); in all due likeness Ninigizibara was envisioned with, or as, a similar instrument Surprisingly, Dumuzi-abzu isn’t the only usually feminine figure who got to replace Dumuzi in the role of Inanna’s spouse in an unusual composition. A single late copy of the lament Uru’amma’irabi (BM 38593) casts Ninigizibara as Inanna’s husband (Wolfgang Heimpel, Balang-Gods, p. 588). Usually this deity was described as a goddess, a harp (or lyre) player and a courtier of Inanna (Goddesses in Context…, p. 115). The unique copy is self-contradictory though, since on one hand an Akkadian gloss interprets Ninigizibara as masculine, on the other the passage itself refers to the deity as a “lady” (gašan), as opposed to “lord” (Balang-Gods, p. 588).

Son turned daughter: Usur-amassu

In contrast with Lisin and Dumuzi-abzu, who both became somewhat malleable simply because they were no longer worshiped, the final major case I’ll discuss is a deity who started as a largely irrelevant figure, but arose to a position of prominence only after their gender changed.

A god named Usur-amassu (“obey his command”, possibly implicitly “obey Adad’s command” given the two are defined as father and son in An = Anum) is first documented in the Old Babylonian period; in other words, roughly when the careers of Lisin and Dumuzi-abzu were already in shambles. As is often the case with minor deities, the earliest evidence are theophoric names, one example being Usur-awassu-gamil. However, it’s worth noting the name was itself a given name in the first place, with prominent bearers including a king of Eshnunna (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period, p. 229)

Uruk in the late first millennium BCE (artefacts-berlin.de; reproduced here for educational purposes only, in accordance with the terms of use)

Usur-amassu at some point came to be worshiped in Uruk. The oldest source attesting to this is a short text commemorating the dedication of a field by Kaššu-bēl-zēri, who served as a governor of the Sealand. Sadly nothing about the text makes precise dating possible; however, the element Kaššu is fairly rare in personal names, and was only in the vogue for a couple of decades, roughly between 1008 BCE and 955 BCE (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 225-226). However, in this city Usur-amassu was regarded as a goddess, not a god. This is surprising, as the name is grammatically masculine - and the person “asked” to obey is supposed to be the bearer (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 229).

It should be noted this is hardly the only case where the grammatical gender of a name doesn’t match the gender of a deity, though. As I discussed in the article about Inanna and gender linked in the lead, the name Ishtar is grammatically masculine despite not only functioning as a feminine theonym but even being the source of one of the two generic words for goddess in Akkadian. Looking further, the husband of Nungal, the goddess of prisons, bore the feminine name Birtum (“fetters”; Antoine Cavigneaux, Manfred Krebernik, Nungal in RlA vol. 9, p. 617; I doubt that we are dealing with a Bronze Age equivalent of a he/him lesbian, though I think it would be a fun way to provide this generally irrelevant deity with more personality). There is also the entire phenomenon of nin names, though it is likely that despite being conventionally translated as “lady”, “mistress” etc. this term was initially gender neutral (Goddesses in Context…, p. 6).

To be entirely fair, we do have clear instances of Usur-amassu’s name being partially modified after the shift in gender - the spelling Usur-amassa occurs in Kaššu-bēl-zēri’s dedication and in Neo-Assyrian sources, and while in the Neo-Babylonian period Usur-amassu predominates, this reflects a change in the feminine possessive pronominal suffix in Akkadian, and thus keeps the name equally feminine. The first element was never adjusted, though, and the expected Usri-amassu (or Usri-amassa) is nowhere to be found (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 228-229).

In at least one case, Usur-amassu’s gender was indicated by the use of a double determinative - the standard dingir (“deity”), which prefaced theonyms, was combined with innin (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 228), a variant of Inanna’s name which could also function as a generic term for goddesses, at least in Uruk (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 122).

It might be worth noting that a somewhat similar practice is documented in Old Babylonian Mari, where dingir could be combined with nin for similar purposes. In a single case this created a minor conundrum for researchers, as one of the deities designated this way (to be fair, only in a single source) is Lagamal (“no mercy”; ironically known well from the personal name Lagamal-gamil, “Lagamal is merciful”), who is otherwise firmly a god. Possibly two unrelated deities with the same name arose in two different cities (Gianni Marchesi, Nicolò Marchetti, A Babylonian Official at Tilmen Höyük in the Time of King Sumu-la-el of Babylon, p. 5)

Paul-Alain Beaulieu assumes that the shift in Usur-amassu’s gender had something to do with her introduction to Uruk and subsequent incorporation into the court of Inanna, and that accordingly the name came to be understood as “obey her (ie. Inanna’s) command)”, though he doesn’t pursue this point further (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 229).

One might be tempted to wonder if perhaps the situation has something to do with Inanna’s oft cited association with change of gender (or at least of gender roles). I personally find this implausible. As I already discussed in the first article from this cycle, in sources which were contemporary with Usur-amassu’s arrival in Uruk this ability tends to be invoked in a highly specific, negative context. “May she change him from a man to a woman” and similar formulas appear as a penalty for oathbreakers in royal inscriptions and treaties, as first attested during the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I. The aforementioned formulas constitute a threat of the loss of a very specific sort of performative masculinity associated with "heroism" or martial valor. More broadly the threat of a change of gender also reflects the fear of a loss of autonomy, something generally tied to masculinity in everyday life in ancient Mesopotamia (Gina Konstantopoulos, My Men Have Become Women, and My Women Men: Gender, Identity, and Cursing in Mesopotamia; Ilona Zsolnay “Goddess of War, Pacifier of Kings”: An Analysis of Ištar’s Martial Role in the Maledictory Sections of the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions).

This is not really a good parallel to Usur-amassu's mysterious "transition". Perhaps most importantly, every single reference to it has humans be affected by the reversal, not gods. There is also no evidence that Usur-amassu was perceived negatively - in contrast with anyone who would hypothetically break a royal oath. Furthermore, nothing really indicates that her role changed alongside her gender. In An = Anum and the incantation series Šurpu the male version is grouped with his brother Misharu (“justice”) and Ishartu (“righteousness”); the sources pertaining to the feminine version from Uruk similarly portray her as a deity of justice, “who renders judgment for the land”, essentially a divine judiciary clerk (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 229). In contrast with martial valor, as far as deities go this role is pretty clearly not really tied to masculinity - or femininity, for that matter (for an overview of judiciary deities and their perception see Manfred Krebernik, Richtergott(heiten) in RlA vol. 11). The change of gender also seemingly didn’t impact Usur-amassu’s preexisting connections, as an inscription from Uruk dated to the reign of Nabonassar explicitly refers to her as a daughter (bukrat) of Adad (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 228).

It’s unclear how Usur-amassu was introduced to the local pantheon of Uruk, but evidently she won over the inhabitants of Uruk pretty quickly. In the Neo-Assyrian period she was one of the deities representing the city during coronations of Assyrian rulers (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 227). In the following Neo-Babylonian period she was one of the five main deities of the city, next to Inanna/Ishtar, Nanaya, Urkayitu (“the Urukean”, an epithet of Inanna turned into a personification of the city) and Bēltu-ša-Rēš (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 179). Thanks to Usur-amassu’s reasonably prominent position in the pantheon of Uruk, she is well represented in the Eanna archives, which document assorted paraphernalia prepared for statues representing her (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 230-244). As a curiosity I feel obliged to point out that in one case a necklace belonging to Usur-amassu was loaned for a festival of Dumuzi (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 335-336). Alas, this evident prominence is not really reflected in publications aimed at general audiences, let alone in popculture. Last attestations of Usur-amassu come from the period of Seleucid rule over Mesopotamia. She retained a degree of importance in Uruk, as expected (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 227). The Eanna actually didn’t exist anymore, but like other deities associated with it she was simply moved to the freshly built Irigal instead (The Revival…, p. 90). Regardless of whether the shift in her gender had anything to do with the primary denizen of both temples, evidently their association was close enough to keep Usur-amassu afloat for the final few centuries of the city’s history.

Postscriptum

This article was initially intended as a pride month special in… 2023? Possibly earlier? I ended up abandoning its original form for a time, and eventually cannibalized its two most major sections, dealing with Shaushka, Ninsianna and Pinikir, for the recent article about Inanna, deities associated with her, and gender. I couldn’t just discard the rest, though, and now you can finally read it all. Much of the information is already on wikipedia through my long term efforts, but now it’s also accessible here, with some extra speculation as a bonus. While this is ostensibly a pride month special, technically none of the sources discussed are really focused on lgbt matters, unless you squint really hard at the two unusual passages I brought up in Dumuzi-abzu’s section. However, I still think the topic of deity gender changes is interesting - if nothing else, it shows that gender was no less malleable than any other aspect of a deity’s character under the rain circumstances. And the process cannot always be neatly explained.

Furthermore, nothing really prevents one from trying to rationalize the changes as a reflection of the respective deities’ identities in a work of fiction featuring them. It’s important to remember that Mesopotamian gods were reinterpreted to meet the needs of new audiences many times, with contemporary institutions, social phenomena or geopolitical developments projected back into the mythical past, especially in literary works (attributing downfall of legendary rulers to insufficient devotion to Marduk is particularly funny, seeing how late his rise to prominence was). Trying to condense Lisin’s puzzling history into something coherent and making him a trans man in the process would thus, arguably, be just a modern example of a similar phenomenon. As long as you don’t alter the content of the actual historical sources, this sort of playful engagement with the material seems more than fine.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning from the beacon ama that both Noshir AND Abu's first pick for downfall was Asmodeus is so funny to me. Everyone wants to be him <3

Unfortunately for them, there can only be one Lord of the Hells, and his name is Brennan Lee Mulligan.

#cr spoilers#critical role spoilers#cr downfall#beacon#beacon ama#cr asmodeus#the lord of the hells#asmodeus cr

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intro. 00:00 Wojciech Golczewski-Otherworld 00:41

Survey Channel-Moss Tilt 03:39

Subphotic-The Sitting Tree 05:12

Chapter 1 12:26 Drapizdat, Reather Weport-Pattern #5 14:59

Minimal Drone*GRL-Lady Of The Mountains 17:56

Hyperlink Dream Sync-Galaxy Structure 22:42

MiDi BiTCH-Unearthly 26:48

Panama Fleets-Zealandia 31:25

Abu Ama + BedouinDrone-Leptis Magna 35:41

Chapter 2 49:03 Lo Five-Unbecoming You 50:58

Time Rival-Redox 55:41

Eje Eje-Saved From The Jazz (Spring) 58:26

Hello Meteor-Waterproof Thoughts 1:01:57

S U R V I V E-Hourglass 1:05:28

Depeche Mode-Don't Say You Love Me 1:09:48

Chapter 3 1:13:19 Vic Mars-Holloways 1:14:59

Pabellón Sintético-Ludwing 1:19:32

Joel Grind-Fallen Metropolis 1:28:27

ATA Records-Pineapple Diode Daiquiri 1:32:18

Mary Lattimore, Roy Montgomery-Blender in a Blender 1:34:45

Off Land-Numbers Station 1:41:04

Chapter 4 1:47:42 Robohands-Palms 1:49:33

Conflux Coldwell-Earth Sea and Sky 1:52:17

Outro 5 1:57:20

Album of background soundscapes by me

#Wojciech Golczewski#Invada#Survey Channel#Music Is The Devil#Subphotic#Drapizdat#Reather Weport#Not Not Fun Records#Minimal Drone*GRL#Bricolage#Hyperlink Dream Sync#Fonolith#business casual#MiDi BiTCH#Cyclical Dreams#Panama Fleets#Abu Ama + BedouinDrone#Mahorka#Unexplained Sounds Group#Lo Five#Castles in Space Subscription Library#Castles In Space#Time Rival#Triplicate Records#Eje Eje#Batov Records#Hello Meteor#S U R V I V E#Holodeck Records#Depeche Mode

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peş peşe Estonya’ya ve Birleşik Arap Emirlikleri’ne gidince neden Avrupa ülkelerindeyken kendimi başka hiçbir şey değil de sadece insan gibi hissettiğimi daha iyi anladım.

Öncelikle, Türkiye’deki ve çeşitli Avrupa ülkelerindeki havalimanlarının arasındaki farklar uzun süredir dikkatimi çekiyordu, BAE’de de olayın çok farklı olmadığını görme imkanına eriştim. Finlandiya (Helsinki), Hollanda (Amsterdam), Estonya (Tallinn), Belçika (Brüksel) ve gittiğim diğer şehirlerdeki havaalanları o kadar minimal ve dümdüz ki bu yapıları inşa eden uzmanların tek derdinin “insanlar işini kolay halletsin” olduğunu net bir şekilde hissedebiliyorsun. Gösterişten uzak, dümdüz, bizdeki tren garlarını andıran ulaşım merkezleri hep böyle; dev bir alışveriş merkezini andırmıyorlar. Benim İstanbul Havaalanı’nda sırf alan çok büyük diye uçağa yetişememişliğim, uçağı kaçırmışlığım var ama Avrupa’nın çoğu ülkesinde bu neredeyse imkansız çünkü her şey çok basit ve mekanik. Ülke ne kadar kalkınmış olursa, havaalanlarının karmaşıklığı o kadar azalmış oluyor. Abu Dhabi havaalanı Sabiha Gökçen’den, Esenboğa’dan ve İstanbul Havaalanı’ndan farksız. Işık ışık ışık, mağaza mağaza mağaza, insanı ayakta si*meyi bekleyen alışveriş noktaları ve cafeler, vesaire vesaire. O nedenle bir ülkenin havalimanı, o ülkenin sosyo-ekonomik durumu başta olmak üzere daha biiiir sürü şeyi hakkında ipuçları yakalayabileceğiniz ilk yerlerden biri diye düşünüyorum. Umurlarında değil yani, senin havaalanında bırakacağın dövize hiç ihtiyaçları yok. Bana kalırsa BAE’nin de olmamalı ama nedense kalkınmışlıklarını havaalanlarına yansıtamamışlar. O da direkt orta doğu kafasından kaynaklanıyor bana göre. Ne kadar kalkınırsan kalkın, bazı eğilimlerinden vazgeçemiyorsun.

Avrupa’da insan gibi hissediyorum çünkü havaalanları dahil olmak üzere hiçbir müzenin, merkezin, kurumun VIP girişi yok. İstediğin kadar varlıklı yahut yoksul ol, bir yere herkes nereden giriyorsa sen de oradan giriyorsun. Sıra mı beklenecek, bekliyorsun. Mekanlarda vale hizmeti yok, bir insana para verip karşılığıda hayatını diğer insanların hayatından daha konforlu hale getirmeni sağlayacak hiçbir hizmet yok. Bir yerde yemek yiyecek, bir şeyler içeceksen “pahalı mıdır, lüks müdür, param yeter mi” diye düşünmek zorunda kalmıyorsun çünkü ayakta s*kilmiyorsun, fiyatlar çok standart. İstersen çok göz alıcı bir yerde otur, istersen son derece salaş; kahveye ödediğin para genelde aynı veya çok benzer.

Marketlerdeki ürünlerin fiyatları arasında dev uçurumlar da yok, hatta neredeyse hiç fark yok. Atıyorum - bu yağ 50 euro, aynı yağ çeşidinin şu markası da 10 euro, gelir durumuna göre seç beğen al değil orada durumlar. İstersen cebinde milyonların, istersen azıcık paran olsun; herkesle aynı ürünü satın alıyorsun çünkü fiyatlar da kalite de çok standart. Türkiye’deki durumları zaten biliyorsunuz, BAE’de de durum farklı değil, hatta daha beter. Ben bizim ülkemizde görmediğim kadar fazla VIP girişi gördüm gittiğim her yerde mesela. Müzeye standart bir fiyatla gireceksin “bugün bilet kalmadı ama 160 dinar yerine 400 dinar verirsen seni hemen özel girişten sokarız ve şu şu avantajları görürsün” diyorlar. Gittiğim iki farklı yerde de aynı şeyle karşılaşınca (Gelecek Müzesi ve Burj Khalifa) aha dedim, muhtemelen buranın alışkanlığı bu yani…

Tüm bu nedenlerden dolayı, özellikle Kuzey Avrupa insanının “çok çalışıcam, zengin olucam, parayı kırıcam” gibi bir derdi yok. Çok zengin de olsan standardın değişmeyecek çünkü. Para hırsıyla yanıp tutuşmadıkları için, bizim köpek gibi çalışmaya harcadığımız vakti onlar türlü aktivitelere, kendi hobilerine, sosyal etkinliklerine falan ayırıyorlar ve tam da bu yüzden o kadar mutlular. Hani genel bir kanı vardır ya “tabii paraları var, mutlular” diye; hayır abi paraları var diye mutlu değiller, paraları olmasa da “insan” gibi yaşamaya devam edeceklerini bildikleri için mutlular.

Letonya’da kaldığımız gece Ali’yle evin altındaki bara bir şeyler içmeye inmiştik. Öncesinde birkaç günü Estonya’da geçirmiştik ve ben sessizliğe, sükuna bir anda fazla alışmışım. Dışarıda sigara içerken o sessizliği yarıp geçen bir araba motoru sesi duyduk ve otomatik olarak kafamızı sesin sahibine çevirdik. Koyu füme, son model bir spor araba, sarı plakasında da kocaman “HABIBI” yazıyor. Ben direkt “ulan bu görgüsüzlüğü başka kim yapabilirdi ki”ye bağladım tabii. Fazla kınamış olacağım ki öngörülmedik bir şekilde yolum BAE’ne düştü. Ha bu vesileyle o kadar da görgüsüz olmadıklarını anladım. Aslında Abu Dhabi ve Dubai’deki çoğu binanın gereksiz seviyede gösterişli ve abartılı olması da bir görgüsüzlük belirtisi olarak nitelendirilebilir ama size yemin ederim, insanları mükemmel. Beni rahatsız edebilecek, huzursuz hissettirecek tek bir bakışa, ufacık bir şeye bile maruz kalmadım ki kendi ülkemde sırf saç rengimden / kolumdaki dövmelerden ötürü yanımdan geçip giden insanların bile laf atışlarına maruz kalırım. Çok benlik yerler değil çünkü ben tarihi alanları gezmeyi, gezeceğim / gezdiğim bu tarihi yerleri oturup okumayı seviyorum ve takdir edersiniz ki yakın geçmişte çölden bozma olarak gelişmiş bir ülkede tarihi yapılara rastlayamıyorsunuz lakin insana güvende hissettiren, rahat bir nefes aldıran bir yer olduğu kesin. Sizi temin ederim ki Arapların, en azından BAE’de yaşayanların büyük bir kısmı aşırı saygılı, görgülü ve özgürlükçü insanlar. Bu paragraf da kendi ön yargılarımın eleştirisi olarak buracıkta dursun.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

List of Mesopotamian deities✨

Mesopotamian legendary beasts ✨

☆Battle Bison beast - one of the creatures slain by Ninurta

☆The eleven mythical monsters created by Tiāmat in the Epic of Creation, Enûma Eliš:

☆Bašmu, “Venomous Snake”

☆Ušumgallu, “Great Dragon”

☆Mušmaḫḫū, “Exalted Serpent”

☆Mušḫuššu, “Furious Snake”

☆Laḫmu, the “Hairy One”

☆Ugallu, the “Big Weather-Beast”

☆Uridimmu, “Mad Lion”

☆Girtablullû, “Scorpion-Man”

☆Umū dabrūtu, “Violent Storms”

☆Kulullû, “Fish-Man”

☆Kusarikku, “Bull-Man”

Mesopotamian Spirits and demons ✨

☆Alû, demon of night

☆Asag - monstrous demon whose presence makes fish boil alive in the rivers

��Asakku, evil demon(s)

☆The edimmu - ghosts of those who were not buried properly

☆Gallû, underworld demon

☆Hanbi or Hanpa - father of Pazuzu

☆Humbaba - guardian of the Cedar Forest

☆Lamashtu - a malevolent being who menaced women during childbirth

☆Lilû, wandering demon

☆Mukīl rēš lemutti demon of headaches

☆Pazuzu - king of the demons of the wind; he also represented the southwestern wind, the bearer of storms and drought

☆Rabisu - an evil vampiric spirit

☆Šulak the bathroom demon, “lurker” in the bathroom

☆Zu - divine storm-bird and the personification of the southern wind and the thunder clouds

Mesopotamian Demigods and Heroes ✨

☆Adapa - a hero who unknowingly refused the gift of immortality

☆The Apkallu - seven demigods created by the god Enki to give civilization to mankind ☆Gilgamesh - hero and king of Uruk; central character in the Epic of Gilgamesh

☆Enkidu - hero and companion of Gilgamesh

☆Enmerkar - the legendary builder of the city of Uruk

☆Lugalbanda - second king of Uruk, who ruled for 1,200 years

☆Utnapishtim - hero who survived a great flood and was granted immortality; character in the Epic of Gilgamesh

Mesopotamian Primordial beings✨

☆Abzu - the Ocean Below, the name for fresh water from underground aquifers; depicted as a deity only in the Babylonian creation epic Enûma Eliš

☆Anshar - god of the sky and male principle

☆Kishar - goddess of the earth and female principle

☆Kur - the first dragon, born of Abzu and Ma. Also Kur-gal, or Ki-gal the underworld

☆Lahamu - first-born daughter of Abzu and Tiamat

☆Lahmu - first-born son of Abzu and Tiamat; a protective and beneficent deity

☆Ma -primordial goddess of the earth

☆Mummu - god of crafts and technical skill

☆Tiamat - primordial goddess of the ocean

Mesopotamian Minor deities✨

This is only some of them. There are thousands.

Abu - a minor god of vegetation

Ama-arhus - Akkadian fertility goddess; later merged into Ninhursag

Amasagnul - Akkadian fertility goddess

Amurru - god of the Amorite people

An - a goddess, possibly the female principle of Anu

Arah - the goddess of fate.

Asaruludu or Namshub - a protective deity

Ashnan - goddess of grain

Aya - a mother goddess and consort of Shamash

Azimua - a minor Sumerian goddess

Bau - dog-headed patron goddess of Lagash

Belet-Seri - recorder of the dead entering the underworld

Birdu - an underworld god; consort of Manungal and later syncretized with Nergal

Bunene - divine charioteer of Shamash

Damgalnuna - mother of Marduk

Damu - god of vegetation and rebirth; possibly a local offshoot of Dumuzi

Emesh - god of vegetation, created to take responsibility on earth for woods, fields, sheep folds, and stables

Enbilulu - god of rivers, canals, irrigation and farming

Endursaga - a herald god

Enkimdu - god of farming, canals and ditches

Enmesarra - an underworld god of the law, equated with Nergal

Ennugi - attendant and throne-bearer of Enlil

Enshag - a minor deity born to relieve the illness of Enki

Enten - god of vegetation, created to take responsibility on earth for the fertility of ewes, goats, cows, donkeys, birds

Erra - Akkadian god of mayhem and pestilence

Gaga - a minor deity featured in the Enûma Eliš

Gatumdag - a fertility goddess and tutelary mother goddess of Lagash

Geshtinanna - Sumerian goddess of wine and cold seasons, sister to Dumuzid

Geshtu-E - minor god of intelligence

Gibil or Gerra - god of fire

Gugalanna - the Great Bull of Heaven, the constellation Taurus and the first husband of Ereshkigal

Gunara - a minor god of uncertain status

Hahanu - a minor god of uncertain status

Hani - an attendant of the storm god Adad

Hayasum - a minor god of uncertain status

Hegir-Nuna - a daughter of the goddess Bau

Hendursaga - god of law

Ilabrat - attendant and minister of state to Anu

Ishum - brother of Shamash and attendant of Erra

Isimud - two-faced messenger of Enki

Ištaran - god of the city of Der (Sumer)

Kabta - obscure god “Lofty one of heaven”

Kakka - attendant and minister of state to both Anu and Anshar

Kingu - consort of Tiamat; killed by Marduk, who used his blood to create mankind

Kubaba - tutelary goddess of the city of Carchemish

Kulla - god of bricks and building

Kus (god) - god of herdsmen

Lahar - god of cattle

Lugal-Irra - possibly a minor variation of Erra

Lulal - the younger son of Inanna; patron god of Bad-tibira

Mamitu - Sumerian goddess of fate

Manungal - an underworld goddess; consort of Birdu

Mandanu -god of divine judgment

Muati - obscure Sumerian god who became syncretized with Nabu

Mushdamma - god of buildings and foundations

Nammu - a creation goddess

Nanaya - goddess personifying voluptuousness and sensuality

Nazi - a minor deity born to relieve the illness of Enki

Negun - a minor goddess of uncertain status

Neti - a minor underworld god; the chief gatekeeper of the netherworld and the servant of Ereshkigal

Nibhaz - god of the Avim

Nidaba - goddess of writing, learning and the harvest

Namtar - minister of Ereshkigal

Nin-Ildu - god of carpenters

Nin-imma - goddess of the female sex organs

Ninazu - god of the underworld and healing

Nindub - god associated with the city Lagash

Ningal - goddess of reeds and consort of Nanna (Sin)

Ningikuga - goddess of reeds and marshes

Ningirama - god of magic and protector against snakes

Ningishzida - god of the vegetation and underworld

Ninkarnunna - god of barbers

Ninkasi - goddess of beer

Ninkilim - "Lord Rodent" god of vermin

Ninkurra - minor mother goddess

Ninmena - Sumerian mother goddess who became syncretized with Ninhursag

Ninsar - goddess of plants

Ninshubur - Sumerian messenger goddess and second-in-command to Inanna, later adapted by the Akkadians as the male god Papsukkal

Ninsun - "Lady Wild Cow"; mother of Gilgamesh

Ninsutu - a minor deity born to relieve the illness of Enki

Nintinugga - Babylonian goddess of healing

Nintulla - a minor deity born to relieve the illness of Enki

Nu Mus Da - patron god of the lost city of Kazallu

Nunbarsegunu - goddess of barley

Nusku - god of light and fire

Pabilsaĝ - tutelary god of the city of Isin

Pap-nigin-gara - Akkadian and Babylonian god of war, syncretized with Ninurta

Pazuzu - son of Hanbi, and king of the demons of the wind

Sarpanit - mother goddess and consort of Marduk

The Sebitti - a group of minor war gods

Shakka - patron god of herdsmen

Shala - goddess of war and grain

Shara - minor god of war and a son of Inanna

Sharra Itu - Sumerian fertility goddess

Shul-pa-e - astral and fertility god associated with the planet Jupiter

Shul-utula - personal deity to Entemena, king of the city of Eninnu

Shullat - minor god and attendant of Shamash

Shulmanu - god of the underworld, fertility and war

Shulsaga - astral goddess

Sirara - goddess of the Persian Gulf

Siris - goddess of beer

Sirsir - god of mariners and boatmen

Sirtir - goddess of sheep

Sumugan - god of the river plains

Tashmetum - consort of Nabu

Tishpak - tutelary god of the city of Eshnunna

Tutu - tutelary god of the city of Borsippa

Ua-Ildak - goddess responsible for pastures and poplar trees

Ukur - a god of the underworld

Uttu - goddess of weaving and clothing

Wer - a storm god linked to Adad

Zaqar - messenger of Sin who relays communication through dreams and nightmares

Mesopotamian Major Deities✨

Hadad (or Adad) - storm and rain god

Enlil (or Ashur) - god of air, head of the Assyrian and Sumerian pantheon

Anu (or An) - god of heaven and the sky, lord of constellations, and father of the gods

Dagon (or Dagan) - god of fertility

Enki (or Ea) - god of the Abzu, crafts, water, intelligence, mischief and creation and divine ruler of the Earth and its humans

Ereshkigal - goddess of Irkalla, the Underworld

Inanna (later known as Ishtar) - goddess of fertility, love, and war

Marduk - patron deity of Babylon who eventually became regarded as the head of the Babylonian pantheon

Nabu - god of wisdom and writing

Nanshe - goddess of prophecy, fertility and fish

Nergal - god of plague, war, and the sun in its destructive capacity; later husband of Ereshkigal

Ninhursag (or Mami, Belet-Ili, Ki, Ninmah, Nintu, or Aruru) - earth and mother goddess

Ninlil - goddess of the air; consort of Enlil

Ninurta - champion of the gods, the epitome of youthful vigor, and god of agriculture

Shamash (or Utu) - god of the sun, arbiter of justice and patron of travelers

Sin (or Nanna) - god of the moon

Tammuz (or Dumuzid) - god of food and vegetation

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

aba abe abh abi abo abu acha ache achi acho achu ada ade adh adi ado adu afa afe afh afi afo afu aga age agh agi ago agu aha ahe ahi aho ahu aja aje aji ajo aju aka ake akh aki ako aku al ala ale alh ali alo alu am ama ame ami amo amu an ana ane ani ano anu apa ape aph api apo apu ar ara are arh ari aro aru asa ase ash asi aso asu ata ate ath ati ato atu ava ave avi avo avu az aza aze azh azi azo azu ba bal bam ban bar baz be bel bem ben ber bez bha bhe bhi bho bhu bi bil bim bin bir biz bo bol bom bon bor boz bu bul bum bun bur buz cha chal cham chan char chaz che chel chem chen cher chez chi chil chim chin chir chiz cho chol chom chon chor choz chu chul chum chun chur chuz da dal dam dan dar daz de del dem den der dez dha dhe dhi dho dhu di dil dim din dir diz do dol dom don dor doz du dul dum dun dur duz eba ebe ebh ebi ebo ebu echa eche echi echo echu eda ede edh edi edo edu efa efe efh efi efo efu ega ege egh egi ego egu eha ehe ehi eho ehu eja eje eji ejo eju eka eke ekh eki eko eku el ela ele elh eli elo elu em ema eme emi emo emu en ena ene eni eno enu epa epe eph epi epo epu er era ere erh eri ero eru esa ese esh esi eso esu eta ete eth eti eto etu eva eve evi evo evu ez eza eze ezh ezi ezo ezu fa fal fam fan far faz fe fel fem fen fer fez fha fhe fhi fho fhu fi fil fim fin fir fiz fo fol fom fon for foz fu ful fum fun fur fuz ga gal gam gan gar gaz ge gel gem gen ger gez gha ghe ghi gho ghu gi gil gim gin gir giz go gol gom gon gor goz gu gul gum gun gur guz ha hal ham han har haz he hel hem hen her hez hi hil him hin hir hiz ho hol hom hon hor hoz hu hul hum hun hur huz

iba ibe ibh ibi ibo ibu icha iche ichi icho ichu ida ide idh idi ido idu ifa ife ifh ifi ifo ifu iga ige igh igi igo igu iha ihe ihi iho ihu ija ije iji ijo iju ika ike ikh iki iko iku il ila ile ilh ili ilo ilu im ima ime imi imo imu in ina ine ini ino inu ipa ipe iph ipi ipo ipu ir ira ire irh iri iro iru isa ise ish isi iso isu ita ite ith iti ito itu iva ive ivi ivo ivu iz iza ize izh izi izo izu ja jal jam jan jar jaz je jel jem jen jer jez ji jil jim jin jir jiz jo jol jom jon jor joz ju jul jum jun jur juz ka kal kam kan kar kaz ke kel kem ken ker kez kha khe khi kho khu ki kil kim kin kir kiz ko kol kom kon kor koz ku kul kum kun kur kuz la lal lam lan lar laz le lel lem len ler lez lha lhe lhi lho lhu li lil lim lin lir liz lo lol lom lon lor loz lu lul lum lun lur luz ma mal mam man mar maz me mel mem men mer mez mi mil mim min mir miz mo mol mom mon mor moz mu mul mum mun mur muz na nal nam nan nar naz ne nel nem nen ner nez ni nil nim nin nir niz no nol nom non nor noz nu nul num nun nur nuz oba obe obh obi obo obu ocha oche ochi ocho ochu oda ode odh odi odo odu ofa ofe ofh ofi ofo ofu oga oge ogh ogi ogo ogu oha ohe ohi oho ohu oja oje oji ojo oju oka oke okh oki oko oku ol ola ole olh oli olo olu om oma ome omi omo omu on ona one oni ono onu opa ope oph opi opo opu or ora ore orh ori oro oru osa ose osh osi oso osu ota ote oth oti oto otu ova ove ovi ovo ovu oz oza oze ozh ozi ozo ozu pa pal pam pan par paz pe pel pem pen per pez pha phe phi pho phu pi pil pim pin pir piz po pol pom pon por poz pu pul pum pun pur puz ra ral ram ran rar raz re rel rem ren rer rez rha rhe rhi rho rhu ri ril rim rin rir riz ro rol rom ron ror roz ru rul rum run rur ruz sa sal sam san sar saz se sel sem sen ser sez sha she shi sho shu si sil sim sin sir siz so sol som son sor soz su sul sum sun sur suz ta tal tam tan tar taz te tel tem ten ter tez tha the thi tho thu ti til tim tin tir tiz to tol tom ton tor toz tu tul tum tun tur tuz uba ube ubh ubi ubo ubu ucha uche uchi ucho uchu uda ude udh udi udo udu ufa ufe ufh ufi ufo ufu uga uge ugh ugi ugo ugu uha uhe uhi uho uhu uja uje uji ujo uju uka uke ukh uki uko uku ul ula ule ulh uli ulo ulu um uma ume umi umo umu un una une uni uno unu upa upe uph upi upo upu ur ura ure urh uri uro uru usa use ush usi uso usu uta ute uth uti uto utu uva uve uvi uvo uvu uz uza uze uzh uzi uzo uzu va val vam van var vaz ve vel vem ven ver vez vi vil vim vin vir viz vo vol vom von vor voz vu vul vum vun vur vuz za zal zam zan zar zaz ze zel zem zen zer zez zha zhe zhi zho zhu zi zil zim zin zir ziz zo zol zom zon zor zoz zu zul zum zun zur zuz

16 notes

·

View notes